In January 2017, the Swiss National Science Foundation organized the Progress Report Meeting of the National Research Programme 69 on Healthy Nutrition and Sustainable Food Production. During the first group discussion, I was probed for the highlights of our own NRP69 project “Environmental-economic models for evaluating the sustainability of the Swiss agri-food system”. Well, highlights, there are many, and work is still ongoing. But the group facilitator would take no prisoners and hear none of the usual research talk along the lines of “you know, we are not sure yet, we still need to check, etc.“. So eventually, I surrendered and said that one of the highlights arising from the dynamic modeling part of our project was that shifts towards more vegetarian diets, that is, reductions in meat consumption, could (I emphasize that they could, not that they would) lead to actual increases in bovine meat production. Increases are really are and happen only under extreme conditions. But what seems to be really robust is the observation that bovine meat production goes down much less (in the long run) than what one would expect given the shift in consumption. I am talking here about bovine meat and not about pork, chicken, fish or any other sort of livestock products. And I consider here the specific case of shifts to vegetarianism where protein uptake from meat consumption is at least partially substituted by dairy products.

Meat consumption, especially bovine meat, has long been criticized for its negative environmental and health impacts. Our own NRP69 data from an environmentally extended input-output table clearly shows that the environmental intensity of the economic value added in the cattle sector is enormous. It should, thus, be logical to recommend a reduction in bovine meat consumption.

Saying that the reduction could lead to an actual increase in bovine meat production sounds fairly counter-intuitive. Doesn’t it? But it is much less so if we take a closer, systemic look at the process through which bovine meat is produced. Given my affinity to system dynamics, when I say process, I mean the stock and flow structure that determines how many feeder cattle farmers keep over time. So then, this bold title that there can be no milk without bovine meat becomes a tale about stocks, flows and mass balance.

When shifting from meat consumption towards a vegetarian diet, the uptake of protein from meat is substituted by plant-based protein sources such as pulses as well as dairy products and eggs. Now, when consumer preferences shift considerably towards vegetarian diets that include dairy products, some interesting dynamics are triggered.

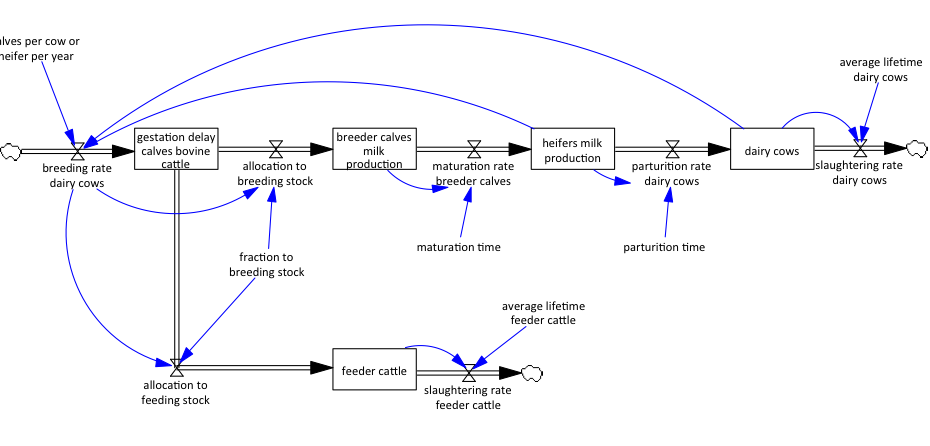

Let’s have a look at herd structures for bovine cattle in the graph below. I am leaving out the herd structure for suckler cattle here as the number of suckler cows in Switzerland is about 15% that of dairy cows (Swiss Farmers Union: Statistische Erhebungen und Schätzungen).

Every year, dairy cows and heifers breed a certain number of calves (“gestation delay calves bovine cattle” in the graph). Dairy cows need to bear one calve per year to maintain milk productivity. Once these calves are born, they either grow up into new dairy cows (moving from “breeder calves milk production” through “heifers milk production”) or they enter the stock of feeder cattle.

Only a limited number of calves can grow into dairy cows. First of all, they need to be female. Then, it is only around every fifth year that a calve is needed to replace a dairy cow (the “average lifetime of dairy cows” being roughly five years). All the remaining calves enter the stock “feeder cattle” and they stay in the stock until they are slaughtered (after the “average lifetime of feeder cattle”).

Visual representation of the herd structure of cattle (excluding suckler cattle). The boxes indicate stocks and the double arrows represent flows that change the stock levels over time.

This stock and flow diagram shows that there is a very tight physical link between milk and bovine meat production. At the moment, this system is quite in balance. But what happens if the demand for bovine meat goes down considerably and is, at least partially, substituted by demand for dairy products?

In the short run, the reduced demand for bovine meat will drive bovine meat price down and thus lower the profitability of bovine meat production. However, because consumers start replacing some of the proteins that they previously got from meat by dairy products, the demand for dairy products will go up. More calves now enter the dairy cow line. Once the reach the heifer and then the dairy cow stock, the somewhat unexpected behavior starts kicking in. As soon as the stock of dairy cows has increased, these cows start having one calve per year, otherwise their milk productivity goes down. As we now have more or less the desired number of dairy cows, we only need one out of five calves to replace our existing dairy cows and to keep the number of dairy cows stable.

And what happens to the other four calves? Well, they enter the feeder cattle stock and even if they are not fattened for a long time, they still generate meat. So much meat that it might be hard to detect a difference in total meat production compared to the time before the shift in consumption…

I have discussed this milk-meat issue with many people and unsurprisingly, encountered quite a bit of resistance. So, again, I am talking about the tight link between dairy products and bovine meat here, not about meat and other animal products in general. I am also not saying that there is no hope in a vegetarian diet from an environmental and health perspective. There is, but it’s just that the biological processes behind milk production have a few surprises in store that make guidelines for dietary patterns a trickier task than assumed. This website, for example, provides more background on meat and dairy consumption.